Russia’s Hidden War Debt Creates a Looming Credit Crisis

Moscow has been quietly pursuing a two-pronged strategy to finance its escalating war costs. In addition to the publicly scrutinized defense budget, it has set up a system of state-directed, off-budget soft loans where the Kremlin badgers banks into making easy credits to defense-sector companies to unofficially fund its war machine.

But with the soaring cost of borrowing that is now becoming a problem that could end in a debilitating crisis, according to a report from the Davis Center at Harvard University.

This lesser-known mechanism, instituted shortly after the invasion of Ukraine, has ballooned, with the volume of loans running into hundreds of billions of dollars. Companies that were forced to take out these loans are starting to squeal from the pain of servicing the rapidly rising interest payments after interest rates climbed into double digits.

Inflation took off, forcing the Central Bank to reverse its loosening of monetary policy in the second quarter of 2023. Since then, prime interest rates have climbed relentlessly to the current all-time high of 21%, imposing crushing interest payments on Russian corporates that have traditionally avoided credits, preferring to make the majority of their investments from retained earnings.

Interest payments eating into profits

The debt burden is now eating up one ruble in four, according to Rostec CEO Sergei Chemezov, and is leading some analysts to predict a wave of bankruptcies later this year, although other economists have argued that Russia’s economy is a lot more robust than it looks.

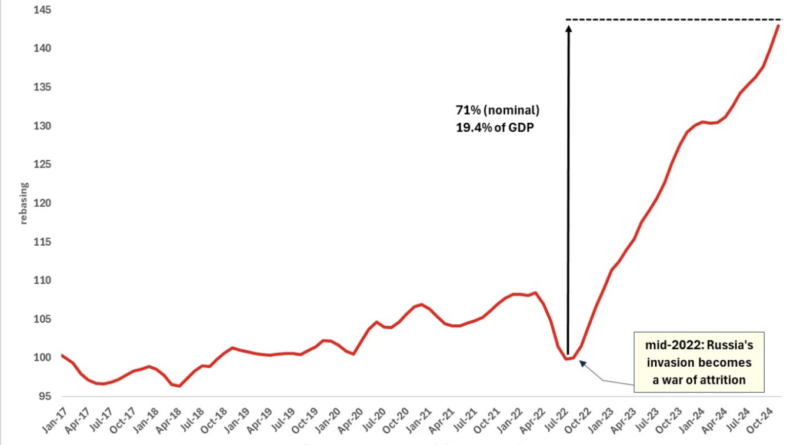

Since mid-2022, this off-budget financing has led to a record $415 billion surge in corporate borrowing, with an estimated $210-250 billion (21-25 trillion rubles) as compulsory loans to defense contractors, said Craig Kennedy, a former investment banker and now an associate of the Davis Center, in a social media post.

Given that Russia’s total defense spending was just over 10 trillion rubles in 2024, this informal state-directed lending to defense companies, according to these estimates, is double all the official military spending — a substantial amount.

Central Bank Governor Elvia Nabiullina has been struggling to bring down inflation as interest rate hikes are clearly not working, so at the end of last year she teamed up with the Finance Ministry to introduce a series of non-monetary policy methods. Among these was effectively reducing retail borrowing by increasing bank macroprudential limits, but she had less success with cutting corporate borrowing, although even that started to slow in the autumn.

The growth of corporate lending slowed to 0.8% year on year in November 2024, down from 2.3% in October 2024, as Nabiullina’s tightening of lending conditions appeared to deliver some results.

Still, even according to the official Central Bank corporate borrowing figure remains elevated at a total outstanding corporate borrowing of 86.7 trillion rubles ($852 billion) in November, up by almost two-thirds (65%) from 52.6 trillion rubles at the start of the war in February 2022. The increase was largely driven by ruble-denominated government-backed loans to industry, according to the Central Bank’s own reporting.

Kennedy estimates that 30% of all this borrowing is due to state-directed lending for military-related contracts.

Kennedy argues that if off-budget lending is added in, the increase in corporate borrowing is much more dramatic.

“This off-budget funding stream is authorized under a new law, quietly enacted on Feb. 25, 2022, that empowers the state to compel Russian banks to extend preferential loans to war-related businesses on terms set by the state. Since mid-2022, Russia has experienced an anomalous 71% expansion in corporate debt, valued at 41.5 trillion rubles ($415 billion) or 19.4% of GDP,” Kennedy says.

“In short, Russia’s total war costs far exceed what official budget expenditures would suggest. The state is stealthily funding around half these costs off-budget with substantial amounts of debt by compelling banks to extend credit on ‘off-market’ (non-commercial) terms to businesses providing goods and services for the war,” writes Kennedy.

Government sources of funding

Bank loans to defense companies are not the main source of funding for Russia’s defense spending. The formal budget expenditure remains the source of funds and thanks to the war boost, revenues rose again in 2024.

For the January-November 2024 period, total revenues reached 32.65 trillion rubles, with oil and gas revenues up by a quarter to 10.3 trillion rubles ($103 billion), while non-oil revenues were also up by a quarter to 22.3 trillion rubles — the Kremlin earned twice as much from non-oil taxes as it did from fuel exports. Currently the oil and gas revenues almost cover all of the defense spending of 10.8 trillion rubles.

Looking ahead, the 2025 budget indicates a further increase in defense spending, with plans to allocate nearly 13.5 trillion rubles (13 billion euros), representing almost a third of federal spending.

The other significant source of budget funding is the approximately 4.5 trillion rubles of Russian OFZ treasury bills issued by the Finance Ministry in 2024 — almost double the amount it used to issue annually pre-war. The total amount of OFZ bonds currently outstanding is around 20 trillion rubles, but that is almost entirely covered by the 19 trillion rubles of liquidity in the banking sector, which is also the main buyer of OFZ.

Finally, the government can tap the National Welfare Fund (NWF), Russia’s rainy-day fund. The amount of cash in the liquid portion of the fund has fallen by half since the start of the war, but in 2024 the Finance Ministry actually managed to increase the amount in reserve slightly. The liquid part of the fund halved from a pre-war 9 trillion rubles to a low of 4.8 trillion rubles in 2023. But this year, the government started with just over 5 trillion rubles and ended the year with 5.8 trillion rubles ($580 billion), leaving the Finance Ministry with a comfortable cushion that can cover the projected budget deficit this year twice over.

Banking crisis on the cards?

Now analysts warn that the amount of accumulated debt may begin to unravel, posing risks to Russia’s financial stability. By maintaining its official defense budget at ostensibly sustainable levels, the Finance Ministry has misled observers and fooled them into significantly underestimating the strain the so-called special military operation is having on the corporate and banking sectors. The off-budget funding scheme is only fueling more inflation, pushing up interest rates, and weakening Russia’s monetary transmission mechanism.

“The Kremlin’s reliance on preferential loans is now driving liquidity and reserve shortfalls in banks and risks a cascading credit crisis,” notes the report. “Interest rates and inflation have surged, with knock-on effects threatening the broader economy,” says Kennedy.

This covert funding method has also left Moscow grappling with an emerging dilemma: delay a ceasefire and risk credit events, such as large-scale bank bailouts, or negotiate while still retaining economic leverage. These risks are of increasing concern to Russian policymakers, who are growing wary of a potential credit crisis undermining domestic stability and their bargaining position in any future peace talks.

The Kremlin’s fiscal fragility provides Ukraine and its allies with a unique opportunity to press for advantageous terms in negotiations. “The financial strain on Moscow has shifted the dynamics, offering unexpected leverage to Ukraine,” the report suggests.

The Russian big business lobbying group, the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP), has been baying for Nabiullina’s blood for months and at the end of last year suggested that the Central Bank “coordinate” its monetary policy with the government and business leaders, suggesting the long-standing independence of the central bank be undermined.

And Nabiullina appeared to cave in December, giving into the pressure, when in a rare dovish surprise decision she kept interest rates on hold at 21%, despite the very widespread expectations of a 200bp rate hike.

NPLs stable but inflation rising

Just before the meeting, Nabiullina defended herself in a speech before the Duma, saying that the CBR was on the verge of an “inflation rate breakthrough” that would become apparent in the first quarter of this year.

Russia’s off-budget defense funding schemes have turned toxic twice before – in 2016-17 and again in 2019-20, the report said. Both times the state had to assume large amounts of bad debt. Will it happen again?

She also pointed to the non-performing loan (NPL) results which amount to only 4% of the loan book and which even declined slightly in October to 3.8%, or RUB3.1 trillion, which have remained largely unchanged all year. Indeed, the level of non-performing debt is now less than 5.51% in 2022 and 6.1% in 2021.

Moreover, corporate NPLs remain adequately covered by prudential reserves at 72% in October, which the CBR said remains a “stable level” compared to the previous month in its November banking update. Banks and companies may be under pressure, but they are not suffering any actual damage – yet. However, a few, like Gazprom, are already at risk; the state-owned gas giant has been borrowing heavily in the last year to cover historic losses after its pipelines were blown up in 2022.

The soft loans are not going to spark a crisis soon. The damage it is doing is more indirect: driving up inflation. The Ukrainian defense budget is some 20% of GDP — 10 times higher than most NATO members. Against that, Russia’s 6% of GDP or circa 10 trillion rubles appears to be prudent given the scale of the conflict. However, if you add in an extra clandestine 20 trillion rubles of spending via the soft loans the true level of military spending is closer to 18% of GDP — on a par with Ukraine — that is pumping the economy full of money.

It is this torrent of money that is causing Nabiullina’s inflation problem and no amount of rate hikes will make any difference, as rising interest rates are supposed to take cash out of the system and cool the economy. But traditional monetary policies don’t work when it is the Kremlin, not the Central Bank, that has its hand on the cash spigot.

“In the second half of 2024, the Central Bank began identifying the state’s preferential corporate lending scheme as a significant threat to Russia’s economic stability,” says Kennedy. “As the main contributor to monetary expansion, it has been driving Russia’s rising inflation. Worse still, because this lending is strategic rather than commercial in nature, the Central Bank observes that it has been largely “insensitive” to interest rate hikes, blunting the CBR’s main tool for combating inflation.”

Credit problems are a gift for Ukraine

“By late 2024, the Kremlin had become aware of the systemic credit risks unleashed by its off-budget defense funding scheme. This has created a dilemma that is likely to weigh on Moscow’s war calculus: the longer it relies on this scheme, the greater the risk a disruptive credit event occurs that undermines its image of financial resilience and weakens its negotiating leverage,” Kennedy argues.

As bne IntelliNews has reported, Ukraine is rapidly running out of men, money and materiel, although it currently has enough to muddle through 2025. But the looming credit problems mean the clock is ticking for Russia too. The military Keynesianism boost to the economy has already worn off and the Central Bank issued a pessimistic medium-term macroeconomic outlook at the start of August that predicts growth will stumble and fall to a mere 0.5% this year. Russia won’t have a crisis this year, but President Vladimir Putin also can’t afford to keep the war machine going indefinitely and from 2025 will be under growing pressure to bring the hostilities to a halt.

On Oct. 28, Putin convened a meeting of senior officials, including the head of the Central Bank, to discuss problems around the “structure and dynamics” of Russia’s “corporate debt portfolio.” Since then, he has publicly shown heightened sensitivity to defense spending levels and the state’s use of preferential lending to achieve “strategic tasks.” This chain of events was capped in December with Nabiullina’s surprise decision to keep rates on hold.

“Unlike the slow-burn risk of inflation, credit event risk — such as corporate and bank bailouts — is seismic in nature: it has the potential to materialize suddenly, unpredictably and with significant disruptive force, especially if it becomes contagious,” the report says.

The Kremlin still has the resources to be able to cope with a credit crisis, but what will be far more damaging is a crisis would strip away the veneer of normality carefully built up by the Kremlin, which has strived to insulate the lives of normal Russians from the effects of the war. That will undermine its hand in mooted talks with Kyiv as well.

“Moscow now faces a dilemma: the longer it puts off a ceasefire, the greater the risk that credit events uncontrollably arise and weaken Moscow’s negotiating leverage,” says Kennedy.

Western tactics going into the talks should include making it clear it is prepared to drag the conflict out as long as it takes until a Russian credit crisis arrives with suitable commitments to a long-term support package for Ukraine. Also to refuse to even discuss sanctions relief that Russia needs to generate more revenues to deal with a mounting pile of deteriorating debt unless there is a comprehensive and “just” peace deal, says Kennedy.

This article was originally published by bne IntelliNews.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.