A Disastrous Black Sea Oil Spill Unites Z-Activists and Anti-War Russians Alike

ANAPA, Russia — Artyom, 21, remembers the night in February when the headquarters for volunteers fighting a fuel oil spill in the Krasnodar region suddenly burst into flames.

“Someone shouted, ‘The headquarters is on fire!’ I didn’t understand what was happening at first. Smoke was billowing everywhere. Volunteers broke down the door and started pulling out hazmat suits and respirators. I called the fire department, but by the time they arrived, everything had already burned down,” Artyom said.

He recalled how volunteers from the ruling United Russia party also helped extinguish the fire that night. Standing nearby was Igor Kastukevich, a Russian-installed senator from occupied Kherson, who had been appointed to oversee the cleanup effort.

“He was cursing loudly and yelling at everyone not to let anyone record what was happening on their phones,” Artyom said. “He already had a grudge against us volunteers. The first time he visited the headquarters, he saw that someone had written ‘Freedom to the seas, fuel oil to the Kremlin’ on the wall in the toilet. He didn’t like that very much.”

Volunteers later discovered a pile of United Russia campaign leaflets among the ashes, Artyom recalled.

“We even joked that it was United Russia activists who set fire to the headquarters and left the message as a hint. But some people are really sure it was them. It is suspicious that a few days before the fire, one of the coordinators of the headquarters was warned that these independent volunteers wanted to be kicked out of here,” he said.

‘Government and oil — fuel oil and death’

A few days before the fire, a banner reading “Government and oil — fuel oil and death” appeared near the Rosneft oil giant’s office in Krasnodar. Police opened a hooliganism case, but the perpetrators were never found.

Small acts of protest like this have sporadically appeared at this site, where volunteers have been tirelessly working for months to clean up one of the worst environmental disasters in recent Russian history.

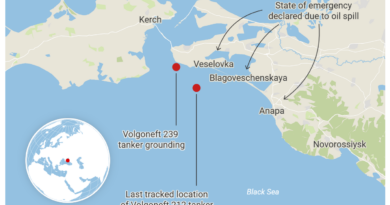

On Dec. 15, 2024, two aging Russian tankers carrying more than 9,000 tons of heavy fuel oil sank during a storm in the Kerch Strait, polluting coastlines from Crimea to Georgia.

Worst-hit by the spill was Russia’s Krasnodar region, where thousands of seabirds, including endangered species, are believed to have died.

Kirill Ponomarev

The spill has sparked an unprecedented wave of independent volunteer efforts from across Russia — and led to widespread public discontent.

Volunteers flocked to the coasts of southern Russia and annexed Crimea from across the country. They included pensioners who had previously sent aid to soldiers, nationalists, ultra-patriotic pro-war activists, United Russia supporters, environmental activists and anti-war Russians, many of whom had taken part in opposition protests in the past.

This independent organizing, taking place outside the purview of the authorities, appears to have irritated officials, who see it as a threat.

Pagans, communists and pacifists

Every morning, a group of young people clad in protective suits painted with anti-war symbols is loaded into an army truck marked with the pro-war “Z” symbol.

Among them are Sasha, an artist with painted nails; Semyon, an 18-year-old anarchist; Liusya, a feminist; and Dasha, an environmental activist.

They travel for half an hour in the rattling truck, listening on a portable speaker to tracks by anti-war musician Noize MC, who is labeled a “foreign agent” by the government.

The driver, Dima, is a soldier who previously delivered humanitarian aid to soldiers and civilians near the front lines in Ukraine.

This surreal scene plays out in Anapa, a small resort city where the fight to save nature has brought people together from across the political spectrum.

“Now that the federal authorities are increasing their pressure on self-organization, it’s really important to find like-minded people on the ground,” said one anti-war volunteer, speaking on condition of anonymity for safety reasons.

He said he has worked alongside members of the far-right nationalist group Russkaya Obshchina (“Russian Community”), pagans, communists, Putin supporters and pro-war “Z-activists” on the beaches.

“Everyone marks their emblems on their protective coveralls somehow. I thought, why not paint a peace sign on mine? I knew a lot of volunteers felt the same way. The next day, a girl I knew did the same. Then another, and another,” the volunteer said. “It’s nice to be among like-minded people.”

Though tensions sometimes arise, volunteers generally get along despite their political differences, he said.

‘The authorities don’t like that we are showing the real situation.’

Environmental activism is one of the few relatively safe ways to express dissent in Russia, which has outlawed anti-war statements and demonstrations since invading Ukraine.

Some volunteers channel broader dissatisfaction with the government into their activism on environmental issues. This includes both opposition activists and apolitical citizens frustrated with the authorities’ handling of the disaster.

“In the first days after the spill, officials acted like nothing had happened. Local residents came to the beaches with shovels to clean up huge layers of fuel oil themselves. The level of self-organization was simply unprecedented. People collected money and humanitarian aid on their own; they bought respirators and protective suits,” said Semyon, the 18-year-old anarchist from Krasnodar.

A few days later, Anapa residents recorded a video appeal to President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, demanding that properly equipped rescuers from across Russia be sent to the polluted areas.

The Krasnodar region did not declare a regional state of emergency until 10 days after the spill on Dec. 25. The federal government followed on Dec. 26, and Crimea declared a regional emergency on Dec. 28 — after nearly two weeks had passed.

An emergency response center in Krasnodar later said nearly 8,500 people, including emergencies ministry staff and volunteers, were involved in the cleanup, along with nearly 400 pieces of heavy machinery.

But once Kastukevich, the senator for occupied Kherson, was appointed to supervise the response, authorities started “tightening the screws,” Semyon recalled.

“Independent volunteer groups were slowly pushed under control, pressured to cooperate or simply forced out,” he said. “Now they’re saying that the emergency regime will be lifted by mid-May. It will be difficult to solve bureaucratic issues without it. Volunteer headquarters will be closed.”

Another volunteer said the head of one of the volunteer groups was forced to leave after authorities threatened him.

“They called and told him the police were going to search his home, and Kastukevich’s people from United Russia threatened to send him to the war because the local authorities were fed up with him,” the volunteer said.

In late January, Natural Resources Minister Alexander Kozlov promised that the beaches in the Krasnodar region would be fully cleaned by the start of the summer, the peak tourist season.

However, in mid-April, the national public health agency reported that 150 Black Sea beaches were still unsuitable for swimming.

While officials insist that the fuel oil spill will soon be fully cleaned up, volunteers remain skeptical.

As the Black Sea warms, oil that has been sitting on the sea floor will rise and wash ashore. The long-term environmental damage will only become clear in the years to come, experts say.

“The authorities want to show that they have everything under control and that the summer holiday season will resume soon,” Semyon said. “We’re trying to show what’s really happening here. Even though the media hype has died down, there’s still a lot of fuel oil. It’s not going away.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an „undesirable“ organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a „foreign agent.“

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work „discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.“ We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.